From an outward appearance, classic cross-country skis look simple in their design. They’re long, skinny, lightweight, and feature a graceful arc that (mostly) spans the length of the ski. However, the reality is that their shape, as well as the techniques used to run them are deceptively complex.

That’s why an understanding of their geometry will not just help you select an appropriate sized ski. That knowledge will also enable you to become a better cross-country skier.

Support Tahoe Trail Guide with a financial contribution via PayPal (single contribution) or Patreon (reoccurring contributions). Your support of Tahoe Trail Guide is very much appreciated!

Like many examples of extraordinary design, classic xc skis reduce the complex nature of their task into the simplest possible form.

Probably the only superfluous element to find on a classic ski is the graphics of the top sheet. Other than that, every aspect of a ski helps the skier overcome friction and gravity as they propel forward.

The three geometrical characteristics of classic cross-country skis are that they’re:

- relatively long

- narrow

- lightweight

Another distinct physical characteristic of classic cross-country skis (related to their weight and shape) is that they lack metal edges.

Length of Classic Cross-Country Skis:

Traditionally, cross-country skis have been excessively long. Now they’re just generally long, at least in comparison to most alpine skis.

The old standard by which to determine your ski length was to reach into the air with one arm while standing. Then, you’d measure the height (length) to your wrist. This is no longer the case, however. Thanks to design advances to the internal structure of classic skis, a shorter ski can bear weight more effectively.

Now the primary determining factor for the length of your skis is your body weight. Remember to add the weight of your clothing and the gear that you’ll be carrying.

I can’t emphasize enough how important it is to be honest about your weight in this context. When renting or buying skis that are designed to bear the weight of a lighter person, you’ll drag the grip zone. This creates excess friction that’ll make even skiing downhill a drag (pun intended).

On the other hand, if you run skis designed for a person heavier than you, you’ll never be able to get any grip. This is a result of not being able to fully compress the ski. In layman’s terms, you won’t be able to move forward!

I was asked this question of appropriate length for classic cross-country skis often while working at Lake Tahoe cross-country ski centers. The answer is simple, but the path to reach the answer is a bit involved.

Every xc ski made by each manufacturer has it’s own specific weight that it will bear. So, the quickest and easiest way to determine your appropriate length of skis is to follow their recommendation. This length will be measured in centimeters.

Using the ski manufacturer’s recommendation is the easiest method to determine the correct length for your classic cross-country skis.

That’s the option I recommend most. That is, unless you’re a more advanced skier and/or have a cross-country ski shop nearby with knowledgeable staff. At those shops with those expert staff, there’s a good chance that they have a flex test machine to determine the exactly correct ski for your body weight and skiing style. However, these are far a few and usually not required for your average cross-country skier.

Using the manufacturer’s recommendation is also the only option you have if you’re forced to buy skis online. The trick is actually finding those recommendation charts. For some reason, manufacturers don’t generally post them on their websites. So, you’ll have to use one provided by a cross-country ski shop online.

Even if all you want is the number, I encourage you to keep reading about how that length is determined. This is because it’ll give you a better understanding of how technique applies to the ski.

Now, If you have access to a gear shop that sells cross-country skis (and the employees know what they’re doing), you might be able to have them perform the “paper test” to determine the correct length of your skis. That is, assuming that they don’t have the aforementioned flex test scale.

There are two parts to this test and both require you and another person. You also need a standard sheet of paper and the actual skis you intend to buy.

And, please, don’t go to a shop and ask them to perform this test for you and then go home to buy those skis online.

First of all, that’s messed up. Secondly, there’s no guarantee that those skis (even identical styles/lengths) are going to have the same flex as the skis you tested in the store. But, mostly importantly, just don’t do it because of the first reason! Small gear shops need all the business they can get, and should be supported when they provide quality customer service.

The first part of the paper test simulates the glide phase when double poling and when skiing straight downhill

- Place both skis on a solid flat surface that (hopefully) won’t scratch the base of the skis.

- Stand on both skis exactly where you would stand if you were wearing ski boots and clicked into the bindings.

- With your weight evenly distributed over both skis, have the other person run the paper under the grip zone. This is the area where you’d find the scale pattern on “waxless” skis.

- The person should be able to slide the paper freely back and forth from the front to the back of the grip zone.

If the person cannot do this, then you’re probably too heavy for those skis. Test the next length of skis. On the other hand, if the person can slide the paper well ahead or behind the grip zone, you’re probably too light for those skis. Test a shorter length of skis.

The second part of the paper test simulates the push-off phase of diagonal striding

- For this part, leave the paper on the floor under one ski.

- Transfer all of your weight to that ski (i.e. stand on just the one ski). Then, have the person try to pull out the paper from beneath the ski in the grip zone area.

If the person cannot remove the paper without ripping it, then those skis are probably fine. At least, so long as you’ve also passed the first test and determined that you’re not dragging the grip zone when standing on both skis. If the person can pull the paper out from underneath the ski, you’re probably too light for the skis.

Keep in mind that this is not 100% accurate. This is because, during the push-off phase, you’d be dynamically compressing the ski rather than simply standing on it like dead weight.

If the other person can, but only slightly, pull out the paper while you’re standing on the one ski it’s probably because your weight is shifting around while trying to retain your balance.

Have the person try to pull out the paper only when you’ve “landed” on that one ski. If this works, you may be okay. However, know that this may also indicate that you need to have exceptional technique in order to effectively use these skis.

Test the next smallest size just in case.

Additional notes to Consider Regarding the Length of Classic Cross-Country Skis:

Low end/lower valued skis tend to accommodate a wide range of weight and are a bit more forgiving. For example, a middle of the road recreational ski might be recommended for a person weighing between 140-175lbs.

In contrast, a racing caliber ski will be more specific (around 10-20lbs of allowance) in regard to the weight it will bear effectively.

For people who are short and heavy or tall people who are very light, you may want to deviate from this process of using only your body weight as a guide in choosing the right length of ski.

Basically, you don’t want to be the shortest person on the longest ski. Or, you don’t want to be the tallest person on the shortest ski. Without going into detail, just know that in both cases your technique will be affected negatively. This is due to the extreme differences in length between you and your skis.

In either case, consider using a ski that’s a little closer to that length of your reach (old method). But it still should be in the ballpark for your weight.

Width of Classic Cross-Country Skis:

Probably the most obvious physical characteristic of classic cross-country skis is their width. They are quite skinny and, in fact, are often referred to as “skinny” skis in the Nordic world.

The narrow width of classic cross-country skis creates a small surface area, thereby reducing friction.

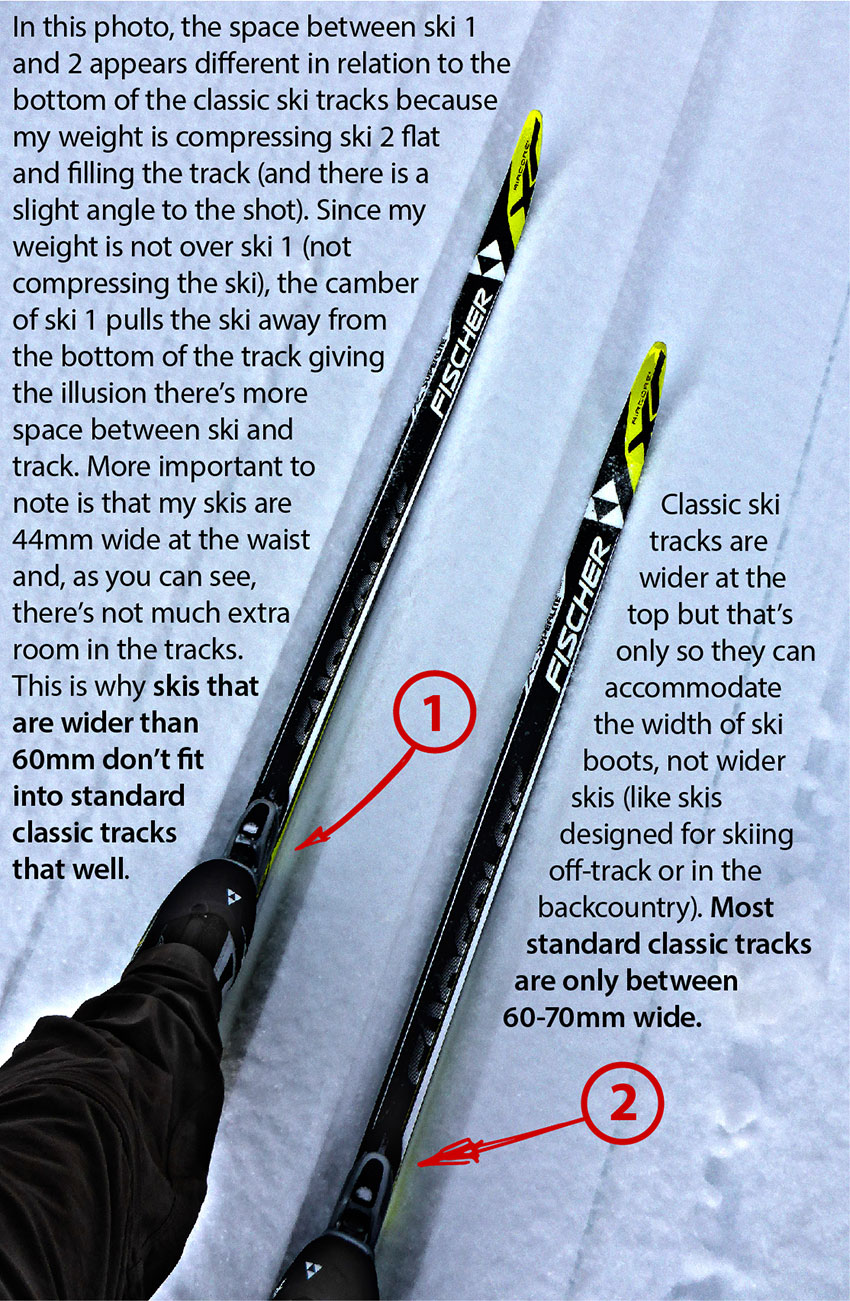

In general, typical classic skis will be between 40-50mm wide. And, they’ll fit easily into the standard tracks (generally 70mm wide) laid by cross-country ski grooming machines.

Beginner-oriented skis of the classic variety will be wider and closer to the 50mm mark, sometimes beyond. The wider ski, as you might imagine, will provide a little more stability for an inexperienced skier. At least up until a certain width. Once you get too wide, you’ll have to exert more pressure on the ski in order to edge it.

Another aspect of width that contributes to the efficiency of a classic ski is its lack of a pronounced sidecut.

The term sidecut refers to the variation in width along the length of the ski.

The three places along the ski that are measured to determine this value are:

- tip

- waist

- tail

Often the measurement will be printed in the graphic on the top sheet of the ski and read tip-waist-tail (i.e. 41-44-44, 48-44-46, 43.5-43-41). All of the numbers are represented in millimeters. Please note that this is different than the measurement used for the length of the ski (centimeters).

In the first example (41-44-44), the tip is actually narrower than the rest of the ski. This shape is often referred to as having an “arrow” shape. The other example (48-44-46) features a more traditional sidecut ratio where the waist is narrower than the tip or tail of the ski. In the case of the third example (43.5-43-41), the ski progressively becomes more narrow from tip to tail. This is said to have a “V-shape sidecut.”

For all intents and purposes, however, these examples illustrate that cross-country skis are essentially straight. A few millimeters of difference between any of the aspects of the ski is not a huge factor. This, especially when considering the overall length of the ski.

With regard to the skis I run, that “curve” spans 192cms. Until you progress beyond beginner or intermediate, you probably won’t notice much of a difference between these shapes.

Classic cross-country skis don’t have sidecut to promote economy of movement when traveling in a straight line.

A straight ski will track straight. Cross-country skis that feature a prominent sidecut (such as backcountry xc skis), on the other hand, will behave in a “squirrely” manner. They’ll struggle to stay moving forward in a straight line. This is because the ski is inclined to travel in accordance with its shape. So, if the ski is straight, it will travel straight. If it’s curved, then it will follow that path.

The obvious drawback to this lack of sidecut is that you’ll have to oppose the ski’s inherent nature of traveling straight, when trying to turn. This is why many alpine skiers who try cross-country skiing for the first time freak out when going downhill.

They quickly figure out that:

- Most cross-country skis don’t have metal edges (described below).

- There’s no sidecut with which to initiate a clean parallel turn.

- An xc ski features a double camber. This is in sharp contrast to an alpine ski that has no camber, or even a negative camber in some cases. I’ll discuss camber later.

So, yes, turning while skiing downhill in cross-country skis can be problematic. But just because the skis don’t have sidecut doesn’t mean you can’t turn. There are a number of different types of turns you can use, in fact, but they all require practice.

Weight of a Classic Cross-Country Ski:

Except for some backcountry varieties, cross-country skis weigh next to nothing. Racing skis are well under two pounds. Even the low end models of recreation skis weigh less than four pounds. Steel-toed boots weigh more than that, but you don’t get to glide in those things!

Alpine skiers are always amazed at how light cross-country skis are. I just chuckle and tell them, “Yeah, it’s so you can go uphill that much faster!”

Lighter skis reduce the amount of fatigue you’ll experience.

You won’t be spending so much effort fighting gravity when skiing on the flats and uphill. Imagine the different experience you’d have running a 10k in steel-toed boots rather than a pair of dedicated running shoes.

There is one thing to consider, however, when it comes to the weight of your skis. A lighter ski isn’t necessarily going to be a better ski for you.

Some people actually prefer to feel some weight attached to their feet when cross-country skiing. The reason for this is because a slightly heavier ski will absorb some of your inefficiencies of technique.

Visualize attaching a five-foot long stick made of balsa wood to one of your feet. And, to your other foot, one made of oak. Every little twitch you make with your foot will transfer to that piece of balsa wood. On the other hand, the oak stick will not be nearly as sensitive to your movement.

If you want to run ultra-light (and ultra-expensive) skis, your technique better be impeccable.

Lastly, classic cross-country skis don’t have metal edges. That is, unless they’re classified as some type of off-track touring or backcountry cross-country ski.

The reason regular classic cross-country skis don’t have metal edges is because the metal:

- increases the ski’s weight

- changes its flex characteristics (generally makes the ski stiffer)

- increases the amount of friction the ski will experience in snow

As nice as it is to have those metal edges when skiing in the backcountry while dealing with wind-scoured, sun baked, and crusty snow, the additional control (i.e. friction) that comes from those metal edges only conspires to slow you down on groomed trails.

Unfortunately, no one has yet developed a limited-slip differential option for cross-country skis using those metal edges!

In conclusion, I’ve intentionally omitted the other millions of details about the geometry of classic cross-country skis. My goal was to provide an overview of the topic without bogging you down in excessive detail as us Nordic nerds are want to do. Instead, I want you to have a good starting point from which to conduct further research.

Just remember that:

- The appropriate length of classic cross-country skis is determined by their ability to bear weight without dragging the grip zone when gliding. But you still need to be able to fully compress the grip zone (camber) during push-off.

- The length of a person’s classic skis are related to their weight. However, if you’re extra heavy or light in relation to your height, consider using a ski that’s closer to your reach (old method).

- To determine the correct length of your skis refer to the manufacturer’s weight/length chart. And, if possible, use the paper test.

- A straight classic ski will track straight. One with a more pronounced sidecut will be easier to turn going downhill. But the sidecut will make it more challenging to maintain a straight line when diagonal striding.

- Classic skis are lightweight, allowing you to travel further with less effort. But, too light of a ski can be too sensitive and result in responding (moving or twitching) to your every slightest movement.

Cross-Country Skiing Explained Articles and Videos

Please note that I wrote and produced the Cross-Country Skiing Explained series of articles and videos with the beginner and intermediate cross-country skier in mind. This is the demographic for whom I most often serve(d) while working in the outdoor recreation industry at Lake Tahoe. I basically treat these articles and videos as extensions of the conversations that I have (had) with those customers.

That said, expert skiers probably could take away something of value from these resources. Just know that I don’t address race-oriented philosophy, technique, or gear selection.

Considerations for buying cross-country ski gear (new and beginner xc skiers)

- Intention, Types of XC Skis, and Whether to Buy New or Used (Part 1)

- How Much Gear to Acquire, Evaluate Your Commitment, Value of Taking XC Ski Lessons (Part 2)

- Can One Set of Classic Cross-Country Skis Work for Groomed and Off-Track XC Skiing? (Part 3)

- Can I Use One Set of XC Ski Boots for All of My Cross-Country Skiing Needs? (Part 4)

- Overview of Off-Track and Backcountry Cross-Country Ski Gear

- Invest in Technique More than Gear

Classic Cross-Country Ski Components

- Introduction to Classic Cross-Country Skis (Part 1)

- Geometry of Classic Cross-Country Skis (Part 2)

- The Grip Zone of Classic Cross-Country Skis (Part 3)

- Types of Bindings for Classic Cross-Country Skiing (Part 4)

- Ski Boots for Classic Cross-Country Skiing (Part 5)

- Classic Cross-Country Ski Poles (Part 6)

- FAQs about Classic Cross-Country Skiing

Waxing Your “Waxless” Cross-Country Skis (for beginner and intermediate xc skiers)

- Introduction to Waxing Your Waxless XC Skis

- Step-by-Step Waxing Tutorial

- FAQs About Waxing Your Waxless XC Skis

Cross-Country Skiing Techniques, Demonstrations, and Related Concepts

- Outdoor VLOG (emphasis on the cross-country skiing experience)

- Cross-Country Skiing in Challenging Conditions

- Considerations for Winter Adventure in Lake Tahoe’s Backcountry

- Using the Side-Step and Herringbone Techniques in the Backcountry

- 10 Tips for Spring Cross-Country Skiing in the Backcountry

- 5 Reasons to Love Spring Cross-Country Skiing

- Considerations for Cross-Country Skiing During the Fall and Early Winter

- Discussing the Goal of Becoming a Better Cross-Country Skier and Embracing Backcountry and Groomed Terrain in Pursuit of that Goal

- The Cross-Country Skiing Experience: Immersing Yourself in Winter

Thank you so much for these articles, they are really helpful. If I am going to use a pulk or something similar to carry my child behind me while cross country skiing, should I take that extra weight into account when purchasing the skis ??

Hey Emilia,

Thanks for the kind words. And glad my articles are helpful for you ?

As far as a chariot or pulk goes, don’t factor that into your weight. That chariot is a completely separate thing and won’t add weight to you. Obviously if you end up carrying your child in a kid backpack, for example, you should include that extra weight.

Hope that helps. Let me know if you have other questions ❄❄❄

I have a pair of Trak skis that delaminated. Can they be repaired or are they garbage now?

Hey Margie,

Thanks for the question!

As far as the fate of your Trak skis go… if there was only some minor delamination at the tails (from repeatedly sticking them in the snow over the course of their life, for example), I’d say you might be able to epoxy them back together. However, if the delamination is occurring anywhere else on the ski, I’d be hesitant to try to fix them. I’ve tried to fix a handful of delaminated skis (small sections) in the past, but once that occurs it’s impossible to get them uniform/flat again. And when snow, ice, and water gets into the core of the ski, it’s not really useable anymore.

The only situation where I’d try to fix is, again, if the tails were slightly coming apart. But even at that point, those skis for me would probably become another set of “rock” skis (generally only used in the worst conditions).

Anyway, not sure if that’s the answer you were looking for. But that’s my two cents.

If it fits in your budget and you can find some, I’d recommend just buying a new setup. You’ll be pleasantly surprised at how nice current gear is (especially the boots!).

Thanks again for reaching out. And good luck!

Excellent tutorial. I have been skiing the last 25 years on my moms hand me down Jarvinens 51-48-50 190cms and always had a blast. Yes too long and hard for me to kick back as didn’t weigh enough but all I ever knew. Our parents introduced us to xctry at our place in WPark CO and would have us break trail for them! Anything after that has been easy! Years ago we introduced our own kids here in MI and bought some generic ones. Once in awhile I’d ski with those but hated. So mine finally gave out! Searching to replace. Went to REI and the kind salesperson couldn’t slide the paper at all in the scale zone when standing evenly on them and said they were good for me. Yikes. Our local ski shop closed. So resorting to online info and purchase. This outline is very helpful. I’m 5’3” 108 lbs and love breaking my own trail here in Michigan. I’ll ski groomed but the track is too wide for my comfort. I’d say I’m intermediate for sure. Hint hint if you’re still referring back to this post and have any advice.

Hey Lisa,

Thanks so much for the kind words. Glad you found the info helpful 🙂

And it sounds like you have way more experience than I do with cross-country skiing! haha. I actually grew up in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and then in the Minneapolis/St. Paul area. However, my winter sport was always wrestling 😉 It’s been over the past six years that I’ve absolutely fallen in love with cross-country skiing. I also get pretty obsessed with a thing once I get embrace it. So, it’s basically been a crash-course for me in learning ever since. It’s just so fortunate that I’m around so many high quality resources in the Lake Tahoe area.

Anyway, if you were looking to buy something mostly for off-track/backcountry use, there are a ton of options. I don’t really recommend one brand in particular as it all comes down to the individual’s needs, skills, and type of terrain that they’ll be skiing in. That said, I’ve managed to collect a few pair of Fischer’s off-track/backcountry cross-country skis. I believe they’re line of skis are a bit more firm than some of the other major xc ski manufacturers, so that stiffer camber/flex enables me to diagonal stride a lot more efficiently/effectively in the backcountry. The stiffer ski also deals with variable and harder-packed snow better than a softer backcountry xc ski designed more for powdery descents.

I generally recommend if a person is going to primarily xc ski off-track, to get something that’s wider than 70 mm. Even then, 70 mmm can be pretty narrow depending on snow depth. I’ve had 62 mm, 88 mm, and a larger set of 112 mm off-track xc skis for a few years. The 62 mm is mostly just good for crusty and harder packed snow. Once there’s a few inches of fresh snow, they kind of just become ski/snowshoes as it’s challenging to diagonal stride with them when they’re submerged in snow. They can technically fit in a groomed track as well, but it sounds like you won’t be doing that very often anyway. So, not really a concern.

The most recent pair of backcountry cross-country skis I picked up was the Fischer S-Bound 98, which seems pretty ideal as far as an “all-mountain” xc ski goes. It’s essentially the same sidecut as the Madshus Epoch (formerly the Karhu 10th Mtn Div xc ski). I read that the Fischer version is more stiff, again, allowing me better diagonal gliding properties.

If you do wind up buying online, select the length of ski based on your weight. At 108 lbs, you’ll mostly end up falling into the smallest skis available in those lines of off-track/backcountry cross-country skis. Most of the manufacturers just make a few sizes of them, and the shortest are either 159 or 169 cm. Again, check the weight range for those sizes.

There are a lot of touring-oriented xc skis on the market, but they all seem to be longer and straighter than the beefier types of off-track/backcountry xc skis. Even in Michigan, where you’re probably not dealing with a lot of mountainous terrain, it’s still nice to have some sidecut to play on the smaller hills and stuff.

Let me know if any of that helps you, or if you want some more recommendations.

Thanks so much for reaching out!

Wow, I just acquired this exact pair of skis to get started! As a rookie, I’m trying to take in all info! Question for you or mod–this is considered a classic ski as opposed to a skate ski, correct?

Thanks for the question! Yes, this page is dedicated to classic/traditional cross-country skis that use a grip zone (underfoot) in order to move forward. This series of articles that I’ve written are specifically about classic skis, so please check them out. And, also check out my YouTube channel. I do embed a bunch of the videos here, but at the channel you can see all the stuff I have (in one place).

http://www.youtube.com/jaredmanninen

Let me know if you have other questions!

According to the terminology I am used to, javelin shaped cross-country skis have a sidecut of e.g. 40-44-40, i.e. tip and tail are narrower than the waist. A sidecut of 40-44-44 is according the the same terminology a pointed sidecut.

I think you’re right about the javelin shaped skis. I just found on Fischer’s website the use of the term “arrow-shaped sidecut” in reference to their 41-44-44 sidecut dimensions. Thanks again! You’re keeping me on point 🙂

OK, thanks. Yes, “arrow shaped” is not a bad term. Then we have the plough shape that Atomic uses on skate skis where the waist is wider than the tip, and the tail is wider than the waist.

I just checked Atomic’s website and saw that they list the shape as being a “V-Shape Sidecut.” The funny thing is that they list the width dimensions (tip-waist-tail) as being 41-43-43.5mm. Whoever updates their website wasn’t paying attention and got it backwards. haha

Ha, ha! Yes, backwards it is, or at least a V upside-down! A real V-shape would be interesting, let’s say 46-44-42.

Indeed. ha ha It’s amazing that such a slight difference can yield different qualities.

“In the case of the third example (43.5-43-41), the ski progressively becomes more narrow from tip to tail and is said to have a “V-shape sidecut.””

I believe it actually is 41-43-43.5 for the skis in question and that it is the V-shape that is the misnomer.

I should just contact Atomic to find out, and to tell them to correct their website. Ha ha. If you find a definitive answer in the meantime, let me know. As always, thanks for the feedback!

Yes, contact Atomic, Jared. I will let you know if I find the answer.

I sent a message through their contact form a couple days ago, but still waiting for a reply. I’ll keep researching though 🙂