The Pileated Woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus) is one of my absolute most favorite birds. It’s not necessarily rare or endangered. However, it’s an elusive bird nonetheless. And it’s impossible not to feel wonder and awe when you see one in the wild thanks to its large black body contrasted by a striped face and red-capped head.

Twelve species of woodpeckers have been officially spotted in the Lake Tahoe Basin. This is according to the Tahoe Institute for Natural Science (TINS). And, the Pileated Woodpecker is one of those woodpecker species. It’s unquestionably the largest woodpecker of Lake Tahoe, where I live and study.

Support Tahoe Trail Guide with a financial contribution via PayPal (single contribution) or Patreon (reoccurring contributions). Your support of Tahoe Trail Guide is very much appreciated!

Please note that I originally wrote this article as a script for my accompanying YouTube video. I created that video about Pileated Woodpeckers in August of 2020. I have since restructured and edited the text in order to better present it here in article format. So, you’ll note similarities between the video and this article.

They’re essentially different, yet complimentary, projects at this point. And, this video has many more photos as well as ncie footage of Pileated Woodpeckers in action.

What’s in a Name?

The Pileated Woodpecker’s scientific name is Dryocopus pileatus.

Dryocopus is a two-part word that comes from the ancient Greek. It means either “tree beating” or “tree cleaver.” I’m partial to the latter because cleaving or splitting is exactly what it looks like when Pileated Woodpeckers go to town on a tree. They don’t necessarily hammer or beat at them in a rapid-fire manner like smaller woodpeckers. Rather, they’re deliberate with their strikes and approach the tree from multiple angles as if they were chiseling with an axe or a cleaver. And, the resultant sounds it makes during its work are loud “thuds” as opposed to jackhammer-like tapping sounds.

Pileatus, the second half of its scientific name comes from Latin. And, it means “capped,” which is a reference to the red crest of the bird.

I prefer to interpret Dryocopus pileatus as the Tree Cleaver who wears the flaming-red crown. Why? Because it sounds way more mythical. And, it’s befitting the bird’s status as effectively being the largest woodpecker in North America.

I say effectively because technically the Pileated Woodpecker is only second in size to the elusive and most likely extinct Ivory-Billed Woodpecker (aka the Ghost Bird). There are people who still hold out hope for the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker. However, there hasn’t been a documented sighting of one in the form of a photograph since 1944.

North American Distribution of Pileated Woodpeckers

As a larger bird, Pileated Woodpeckers prefer forests that feature big, old-growth and mature hardwood and coniferous trees. Unfortunately, stands of old-growth trees in the United States are few and far apart due to historical clear cutting practices.

However, according to David Sibley’s latest book “What It’s Like to be a Bird,” #ad in past decades some farmland across North America has been reclaimed by forest. And, much of it has grown mature enough to host Pileated Woodpeckers. So this has led to an increase in their population.

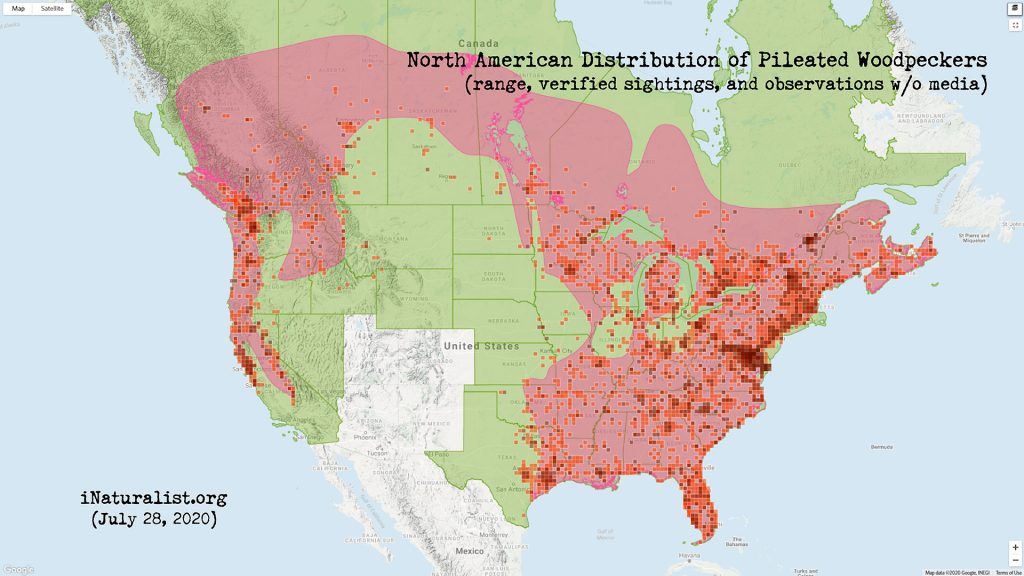

As illustrated by the distribution map of Pileated Woodpeckers in North America, there’s a higher concentration of them on the eastern half of the US. Additionally, there are many living farther north into Canada.

The solid block of color that defines their distribution range looks significant. However, Pileated Woodpeckers are never present in great numbers. There not ever highly concentrated in any one location either. So, their presence across North America is often considered fragmented. This fragmented distribution most likely mirrors the distribution range of those larger, old-growth and mature forests.

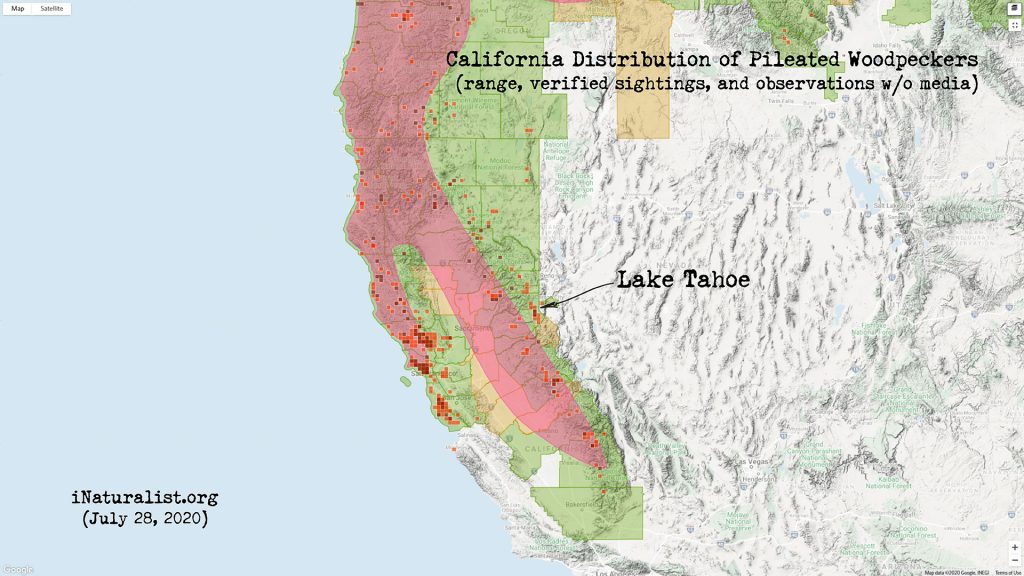

Look even closer at that western edge of the map. You’ll notice a sliver of their range running down from the north along the Sierra Nevada Mountains. For this I’m totally grateful because it indicates that Pileated Woodpeckers living at Lake Tahoe is not an anomaly.

Distribution and Observations of Pileated Woodpeckers at Lake Tahoe

Although there are few examples of old-growth trees at Lake Tahoe, there’s enough of a desirable habitat to accommodate Pileated Woodpeckers.

In fact, there are numerous stands of relatively large and/or decaying trees present around the lake. And those dead trees and snags, many of which are dead due to drought, disease, infestation, or wildfire, are prime targets for Pileated Woodpeckers.

Despite their presence, however, Pileated Woodpeckers are not commonly observed at Lake Tahoe. For example, there are just over 20 observations of Pileated Woodpeckers in the Lake Tahoe Basin between 2012 and 2020 on iNaturalist.

Also, many long-time Tahoe locals have told me that they’ve never seen a Pileated. Or, they’ve only spotted one or two in 20+ years.

I may be more of an anomaly than anything. I’ve been lucky enough to photograph Pileateds on six separate occasions. So six of those 20+ sightings on iNaturalist are mine (use the search option to see all of my Pileated observations). And of my six observations I’m certain two of them are of the same female, just on different dates.

Additionally, some iNat observations are found feathers or excavation sites. They’re not actual observations of Pileateds themselves. 20+ observations may sound like a lot, but when you break down that iNat sampling you can see how relatively uncommon it is to observe a Pileated Woodpecker at Lake Tahoe.

Notes about Bird Data Collection at Lake Tahoe

Please note that the iNaturalist records I’m citing are incomplete. They’re probably only a sampling of total historical observations of Pileated Woodpeckers at Tahoe.

This is due to two factors:

- iNaturalist is a relatively new nature observation website (designed for public use c. 2011)

- for verifiable, or research grade, observations iNaturalist requires photographs or sound clips

So, people have to actually know about iNaturalist and have photos to upload to the website. Compared to traditional birding standards, this is a lot of work.

Historically, the only requirement was to document your bird observations in a notebook. Then, you’d report your “checklist” to a data collecting body such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (via eBird now).

There are, however, problems with eBird data for the Tahoe/Truckee area.

According to Will Richardson (TINS), “the vetting happens at the county level, and since our seven counties in question drop down to much lower elevation, tons of bogus records slip past uncontested.” As an example he states, “Look at something like the American Crow which has become extremely rare here; last I looked there are tons of eBird records here, and I’m sure ≥ 95% are misidentified.”

He acknowledges that these problems are for eBird data in general for the Lake Tahoe Region, not necessarily about Pileated Woodpeckers. However, it would stand to reason that there’d be some inaccuracies if records aren’t being consistently verified for Lake Tahoe.

You can refine the eBird map (link above) to show observations with photos via the “explore rich media” option. Those numbers total around 30 historical observations.

I understand that gathering photographic evidence is not an easy task, especially with elusive, uncommon, or rare species. But in this digital age of technological advances I do often prescribe to the belief that “if you didn’t get a photo, it didn’t happen.”

Excavation Activities of Pileated Woodpeckers

While excavating trees, Pileateds leave behind large oblong or rectangular-shaped cavities. These cavities will often, then, provide nesting areas for a host of other cavity-dwelling wildlife.

But Pileated Woodpeckers don’t just create these cavities for the fun of it. If they’re not establishing their own nesting site, they’re seeking insects that live within the trees.

Woodpeckers often get a bad rap for the perceived destruction they cause to trees. Just look at the size and number of cavities left behind by a mated pair of Pileated Woodpeckers in South Lake Tahoe. These photos, for example, were taken while I hiked roughly a one-mile area of forest. Those holes are huge! And to look at them, you’d think that the Pileated Woodpeckers killed the forest.

But that interpretation is actually backwards.

Those trees were most likely already in a state of decline due to one of the aforementioned reasons. So, the Pileated Woodpeckers wouldn’t have even begun their excavation operations until after these trees began to succumb to whatever caused them to die in the first place.

Pileated Woodpeckers Love Eating Insects

Regardless of the reason for a trees’ demise, insects will always ultimately invade those dead and decaying specimens.

It’s that whole life-cycle process, right?

Organisms working up and down the food chain to create that balance we call nature.

When you have an increased number of insects, you’re also going to find an increased number (or at least increased frequency of activity) of critters who want to eat those insects.

In the above case, the pair of Pileated Woodpeckers have dominated that specific location most likely because of the abundance of food (i.e. insects).

Again, woodpeckers don’t make it a habit of extensively working over a tree that’s not infested with insects. Live and healthy trees generally host far fewer insects so woodpeckers will probe and peck around that tree. But once they determine that there’s not much for them to eat, they’ll move on. No harm, no foul.

Even sapsuckers, who favor live trees for their fresh sap, don’t typically cause permanent damage to trees when creating a system of sap wells.

As an aside, if woodpeckers are causing damage to your house I highly recommend taking a closer look at what’s going on inside your walls.

Pileated Woodpeckers will eat berries and nuts when necessary, but they primarily eat insects. They’re favorite food is Carpenter Ants, with Thatcher Ants coming in a close second.

According to Stephen Shunks’s book “Woodpeckers of North America,” #ad in the western states, Pileated Woodpeckers consume a 3:2 ratio of Carpenter to Thatcher Ants. And across North America, 40-97% of a Pileated’s diet consists of ants. This means that you can often find Pileated Woodpeckers roaming forest floors.

Pileated Woodpeckers’ Paradoxical Personality

Pileateds are often considered secretive and shy, which contributes to the fact that there are relatively few sightings of them at Lake Tahoe. But they’re also considered “fearless” for allowing people to approach them as they forage for food.

The latter example has been my experience during three of my six observations to-date. Each of those three times I was able to walk within 15 feet of them before they decided I was too close for their comfort. They’d fly about 40 feet away and continue their activities. When I’d again walk within 15 feet of them, they’d fly another short distance away.

Usually, I can get away with this type of interaction three or four times before they’re finished tolerating my presence and fly completely away. That’s fine, though, because I don’t like spending too much time observing any one bird as it can stress them out.

Physical Characteristics to Identify Pileated Woodpeckers

The size of a Pileated Woodpecker is approximately that of an American Crow. Some say slightly smaller. But, generally, they’re 16.5 inches in length and have a wingspan of around 29 inches.

Pileated Woodpeckers are primarily black, but display broad patches of white under their wings. This is often most visible when they’re in flight.

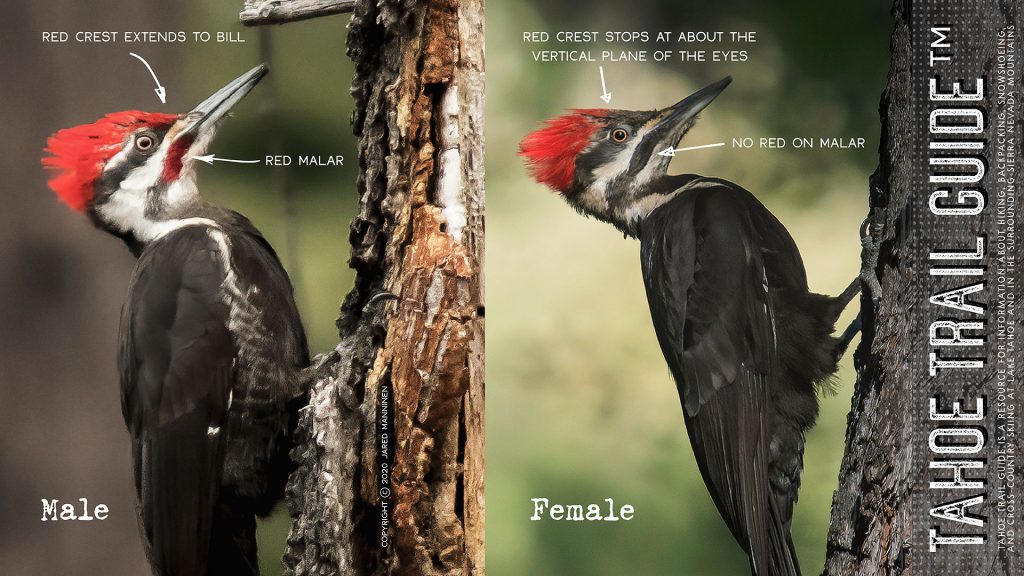

The most striking visual aspect of their appearance, however, is that pileatus part of their scientific name which, is to say, they have that unmistakable red-colored cap. Males and females share this trait. However, the red top of a male extends down its forehead to its bill. On the other hand, the red cap of a female doesn’t extend much beyond the vertical plane of their eyes.

Males also have a red stripe that extends along their malar line. Females don’t have this red stripe on the sides of their face. Instead, they just have a continuous black stripe.

Mating, Nesting, and Territorial Habits of Pileated Woodpeckers

It’s believed that Pileated Woodpeckers mate for life. They’re also known to occupy the same territory during their lifetime. This territory can encompass hundreds of acres of land or span upwards of a square-mile or more.

The examples I showed of the mated pair’s excavation activities was probably created over many years rather than in a single season, for example.

Another interesting fact about Pileateds and their lifestyle habits is that they’ll often reuse the same tree year-after-year for nesting. However, they don’t actually use the same nesting hole. Instead, they create a new cavity each year in the same tree for just such a purpose. And, those nesting holes are usually round compared to their oblong excavation cavities.

Reading between the lines … Pileated Woodpeckers are non-migratory birds. And, even if one of the mate dies the surviving partner will often try to attract another to their existing territory.

What creates a little confusion about this trait is when people observe Pileateds flying outside of their usual territory. But often these “migrating” birds are usually just offspring in search of their own territory.

Pileated Woodpecker’s Call of the Wild

I’d be remiss for not mentioning one of the most defining traits of a Pileated Woodpecker, which is the sounds it makes.

Pileateds drum like other woodpeckers but, as you might expect, much louder.

What really sets them apart from the other woodpeckers, though, is their vocalizations of maniacal sounding laughter. Similar to the calls of a Northern Flicker, but much louder and with a slightly wavering pitch. Pileateds sound this alarming call to denote their territory or to attract a mate.

That laughter combined with its stark facial appearance reinforces, in my opinion, a Pileated Woodpecker’s status as a mythical and fantastic bird.

Unfortunately, I have yet to be able to record a sound clip of that extraordinary “jungle call” of the Pileated Woodpecker. But, you can hear examples at eBird and Xeno Canto.

Family of Four Pileated Woodpeckers

My most memorable sighting of a Pileated Woodpecker occurred on July 16, 2020. I decided to go for a short walk in the woods on my way home from work that evening.

I parked my Jeep and negotiated a short hill nearby. When I reached the top of the hill, barely 10 meters away was a female Pileated chiseling away at a White Fir.

As I sighted in with my camera, I realized she wasn’t alone. Perched nearby was a juvenile female Pileated Woodpecker. The daughter, I assumed. As momma pecked at the tree, the daughter kept an inquisitive eye on her.

Looking beyond the two females and downhill I saw another Pileated! I couldn’t believe it because this time it was a male. The father, I bet.

The two females eventually flew downhill, so I pursued them. And after watching them peck and probe around the deadfalls that littered the forest floor, I decided to search for that male Pileated.

Unbelievably, it was 50 meters away on the side of the hill. And, there was second male! One looked like an adult while the other a juvenile. So, now I not only found the mother and daughter, but the father and son as well.

I began to walk in the direction of the two males. They, however, were not as accommodating as the females. As soon as I snapped a few photos of the boys, they decided they’d had enough of me and flew well out of my range.

I hiked back uphill and watched the two females resume their work on the White Fir for a few minutes.

The day’s light was fading, however, which was reason enough to leave the family to their work and for me to head back home.

Another Short Story of a Pileated Woodpecker

In August of 2020, a Good Samaritan brought a Pileated Woodpecker to Lake Tahoe Wildlife Care. I found this interesting as it was in the middle of me publishing this article, as well as my Pileated Woodpecker video (featured above).

Seeing the Pileated Woodpecker on the facility’s social media account, I called to inquire about it. The volunteer with whom I spoke described the situation.

A person found the Pileated Woodpecker covered in sap and, literally, stuck to a tree. This occurred in Pollock Pines, which is on the “west slope” in El Dorado County. The Pileated Woodpecker suffered damage to its wings and feathers from being fixed to the tree. Hence, the transport to the wildlife care facility in South Tahoe.

The person at the facility then mentioned in our conversation that in all of her years of living in Tahoe and working at the facility, she had never seen a Pileated at Lake Tahoe. Much the same response whenever I mention to other locals my sightings of Pileateds.

Woody Woodpecker is Not Based on a Pileated Woodpecker

One of the last things I wanted to mention about Pileated Woodpeckers is that, contrary to popular believe, Pileateds are not actually the inspiration for the cartoon character Woody Woodpecker. That honor goes to the Acorn Woodpecker in spite of the similar appearances of Woody and Pileateds.

Two versions of Woody’s origin story go something like this …

- Walter Lantz (animator who created Woody) and his wife were amused by an Acorn Woodpecker at a cabin they rented while on vacation in California

- Walter Lantz grew totally irritated at the Acorn Woodpecker, but his wife insisted that he channel his frustration in a healthy way by creating a character out of the bird.

Either way, Woody is not actually based on a Pileated Woodpecker.

Don’t believe me? Read the humorous 2009 NPR article titled “Woody the Acorn (Not Pileated) Woodpecker” by Julie Zickefoose.

Disclaimer

I’m sure there are details about Pileated Woodpeckers that I never touched on, as well as some minor inaccuracies. Just know that I produced this project in good faith and to the best of my current abilities and knowledge.

Feel free to post any feedback or corrections in the comment section below. Perhaps I’ll one day make a follow-up project to include everything I’ve missed in this one.

Articles About Lake Tahoe Plants and Wildlife

The following Tahoe Trail Guide articles feature information, history, and stories about the various forms of plant and wildlife that you can find at Lake Tahoe.

Lake Tahoe Wildflowers

- Two Major Factors that Determine Peak Bloom Times for Wildflowers at Tahoe

- Tips for Finding Wildflowers at Tahoe

- The Sinister Mustard Flower Rust

- Big Yellow Wildflowers with Big Green Leaves called Woolly Mule’s Ears and Arrowleaf Balsamroot

Trees of the Sierra Nevada

Birds of Lake Tahoe

- The Tree Cleaving Pileated Woodpecker

- How Woodpecker Contribute to Healthy Forests at Lake Tahoe (and other fun facts)

Fish of the Sierra Nevada

Creating an Immersive Outdoor Experience

- Cultivating Adventure in Your Daily Life

- Deepen Your Outdoor Experience by Documenting Your Nature-Related Observations

- Considerations and Reasons for Doing a Big Year

Whenever you’re at Lake Tahoe and take photographs of the birds you see,

post them on Instagram using the hashtag Birds of Lake Tahoe.

I’d love to see what you’re finding out there 🙂