For most of us, being outdoors offers two very broad but critical benefits. Nature provides relief from our daily grind. And, it can also inspire us in countless ways. Even just going outside to watch the trees sway in the wind during a ten minute break from work will provide some stress relief. And if you take a brisk walk during lunch, for example, chances are you’re going to experience at least one or two brilliant thoughts. They may be directly related to something you see in nature. Or, you may experience a flash of genius simply because your mind is at ease as a result of being outside.

Regardless of the activity in which we’re participating, there’s just something transformative about being outside. We’re all a part of the earth, after all, so it stands to reason that we need to routinely experience that connection. Otherwise, it’s easy to believe that we were only ever meant to travel from our house to our car to the office (and then back again).

Support Tahoe Trail Guide with a financial contribution via PayPal (single contribution) or Patreon (reoccurring contributions). Your support of Tahoe Trail Guide is very much appreciated!

Obviously, those examples are simplistic. And many of us probably wouldn’t equate a lunch hour stroll in the city with a strenuous hike in the mountains. But nature is all around us no matter what. And that’s the point!

Our lives can be made better simply by going outside. Furthermore, there’s always some specific nature-related observation that we could make by doing so. And it’s these nature observations that can enhance our outdoor experience and deepen our connection to the natural world.

But isn’t just being outside good enough?

What would be the point of documenting those observations?

Reasons and Benefits to Document Your Nature Observations

I totally agree that documenting your nature-related observations sounds a lot like homework. But it’s the good kind of homework because it’s self-driven. You’re in control of what you focus on or study. So it’s really fun!

And you hike or ski or ride your bike for fun, right? Or, I’m willing to bet that you step out of the office for that lunchtime stroll so that you can at least look at something other than a computer screen.

If any of those examples (or variations of them) apply, I think it’s safe to say that you do have some interest in nature. And maybe you’d even like to learn more about what you encounter while being outside.

I don’t know anybody who wouldn’t like to be able to name off the bird or plant species that they see on a hike, for example. It’s very similar to knowing the host language of a new country in which you’re traveling. It’s empowering. And it provides access to deeper and more meaningful experiences.

Believe it or not, I log most of my nature observations while commuting to and from work or running errands in town. I know that I’m very fortunate to live at Lake Tahoe, meaning that I’m surrounded by wilderness. Again, though, nature is everywhere. So you don’t have to spend countless hours grinding out long miles to make some meaningful observations.

I also assume that you have at least one camera with you at all times. If you carry your phone with you everywhere, like I do, you have a camera at your disposal. You probably have a voice note app on your phone, as well. So except for the additional bit of work to take some detailed photos or to record a couple of brief descriptions of your observations, you don’t have many reasons not to document your observations.

Again, I believe that you’ll only enhance your outdoor experience once you start to pay closer attention to nature and record what you see.

Documenting Your Observations…

- encourages you to learn more about the natural world (species names, behaviors, habitats)

- teaches you to look closer and more critically in order to see details more accurately

- helps you retain detailed information and develop better memory recall

- enables you to bring nature home with you (in the form of photos and other recordings)

- allows you to share your experiences with other people (via social media, iNaturalist)

- helps you track the passage of time and seasons (with something other than just a calendar)

- allows you to make comparisons from year-to-year and between seasons

- contributes to citizen science (leading to a better collective understanding of the natural world)

- creates an immersive and intimate outdoor experience (versus passive participants in life)

Pace Yourself When Documenting Your Nature-Related Observations

Taking photos, drawing pictures, or describing in a journal what you see forces you to look closer at a subject rather than just giving it a fleeting glance while walking past it. And this brief pause to study whatever caught your eye is where the magic happens. This is your opportunity to take in details that you would’ve otherwise missed.

That said, unless you’re an actual botanist or wildlife biologist at work don’t document everything you see. You’ll never get anywhere. And, you’ll quickly burn yourself out trying to answer the question asked by every 4-year old on the planet, “What’s this?”

You will have to put in the time if you actually want to learn. But treat this process as a lifelong practice rather than something you have to complete on your next 5-mile hike, for example.

Remember, this approach to experiencing the outdoors is educational but it should be fun. It’s also supposed to enhance your experience whether you’re hiking or skiing, for example, not replace it. So, document what you find most interesting at first and then expand upon that knowledge as you hone your observational skills.

Tools for Documenting Your Observations in Nature

Today, there are numerous ways in which to record your nature observations. They range from old school paper and pencil to AI driven phone apps that’ll identify birds for you based on the songs in which you’re hearing (and recording with your phone).

In the following sections, I provide brief descriptions about some common ways in which to document your observations. I also provide some pros and cons about each method. Just know that these are not detailed how-to instructions. Rather, my goal is to simply point out some basic tools that you could use to begin recording your observations.

Physical Journals

As you might expect, the use of a physical journal is the most historic method of recording observations in nature. Physical journals are immediate, low-tech, and mostly indestructible. So long as you don’t toss it into a campfire or drop it in a lake, your journal will last for many years.

That said, I recommend using a pencil versus a pen because most pens will bleed. And, if given the option, use acid-free (aka archival) paper so that the individual sheets won’t yellow or degrade over time. When faced with inclement weather, protect your journal with a waterproof stuff sack or Ziploc-type plastic bag.

There are three different styles of physical journals that you could keep.

The first is a traditional written journal, one in which you simply describe your observations and experiences in prose. This is the easiest and most immediate option for most people. But information can quickly get buried if you find yourself writing long passages about everything you see. As a result, referring back to a specific detail about an observation can potentially take you a long time to find.

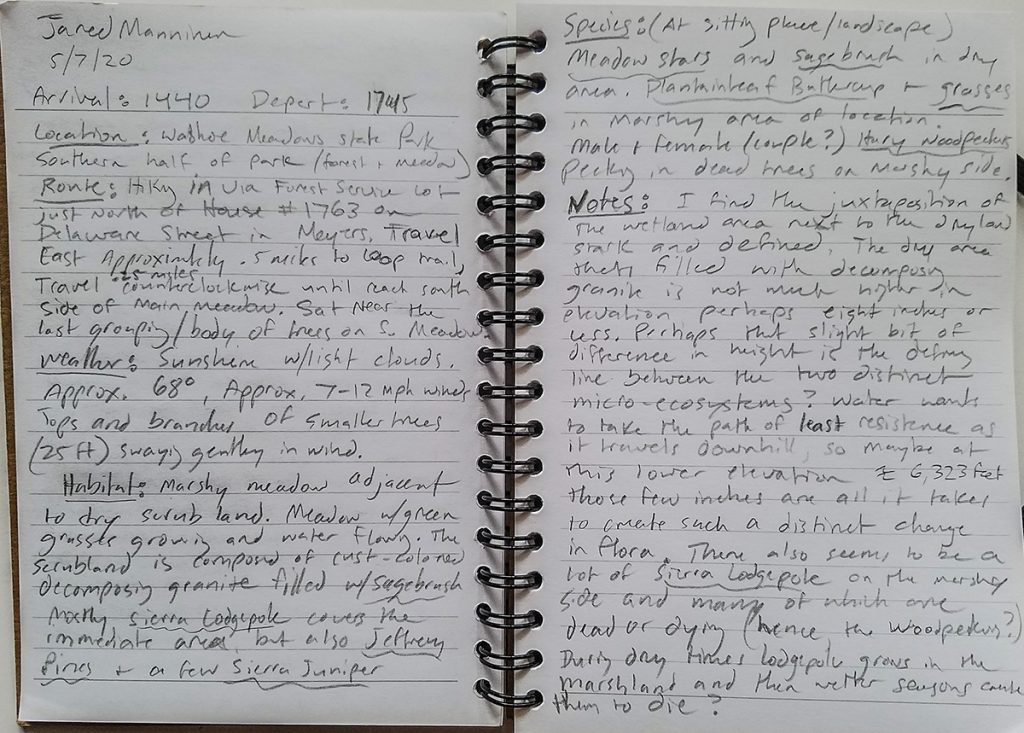

Another option is to keep a field journal. Believe it or not, there’s a standard journal format used by many naturalists to record their observations. This format is a two-page spread. And, on the facing pages, there are specific data fields that you fill in with succinct information about each location, habitat, or micro-climate in which you’re exploring. You could include illustrations in this type of journal. However, because you’re often covering a lot of ground on each spread you won’t have a lot of space for those illustrations. Although you can add more pages to accommodate each location, I’ve found that this essentially undermines the reason for using this particular format. Basically, the defining characteristic of this type of field journal is its uniformity. It’s easy to find information in this journal because every two pages is dedicated to a new location.

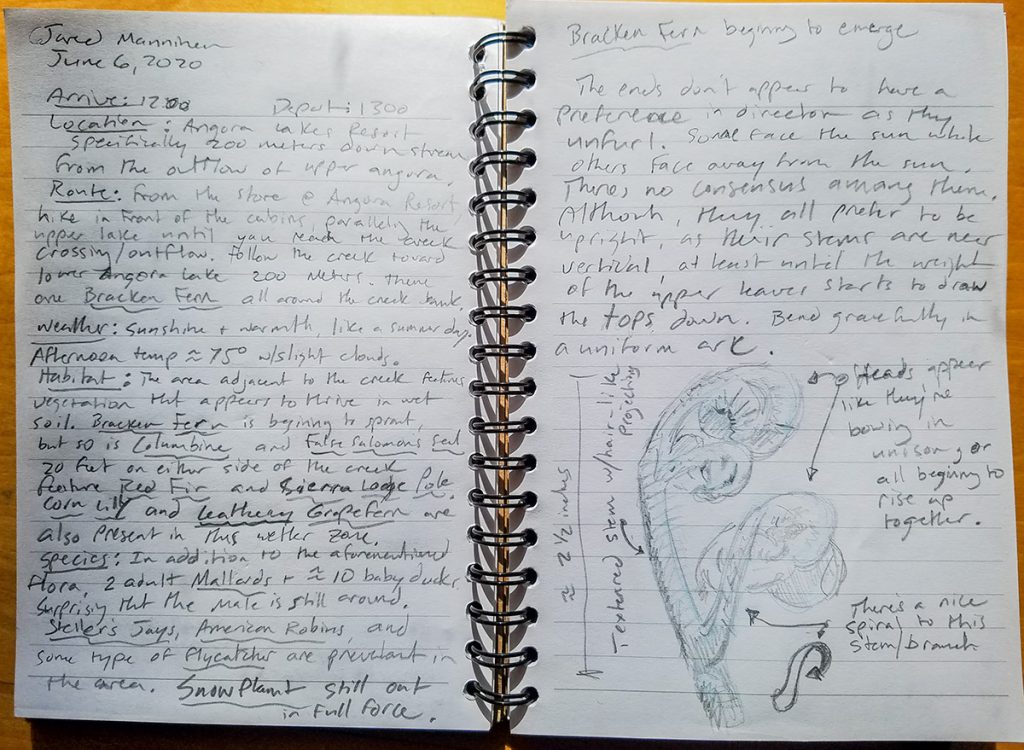

A third option is to keep a nature journal. This style of recording observations is based on creating detailed illustrations of each subject and then using very succinct written descriptions (if necessary). These make for the most beautiful looking journals. And they’re more free-form than a naturalist’s typical field journal. But, clearly, when documenting your observations in a journal of this nature (pun intended) you need some drawing skills. And, as immersive and rewarding it is to create a nature journal, plan on hanging out in one location for a while because you’re not really going to have time to hike. John Muir Laws and Lara Call Gastinger produce amazing nature journals. And, both artists are great resources for learning how to go about beginning your nature journal.

Of course, you can modify and adapt any of the three aforementioned journals to meet your personal needs. Just try to develop some sort of uniformity in your documentation so that you can quickly reference your observations down the road.

Computer Software

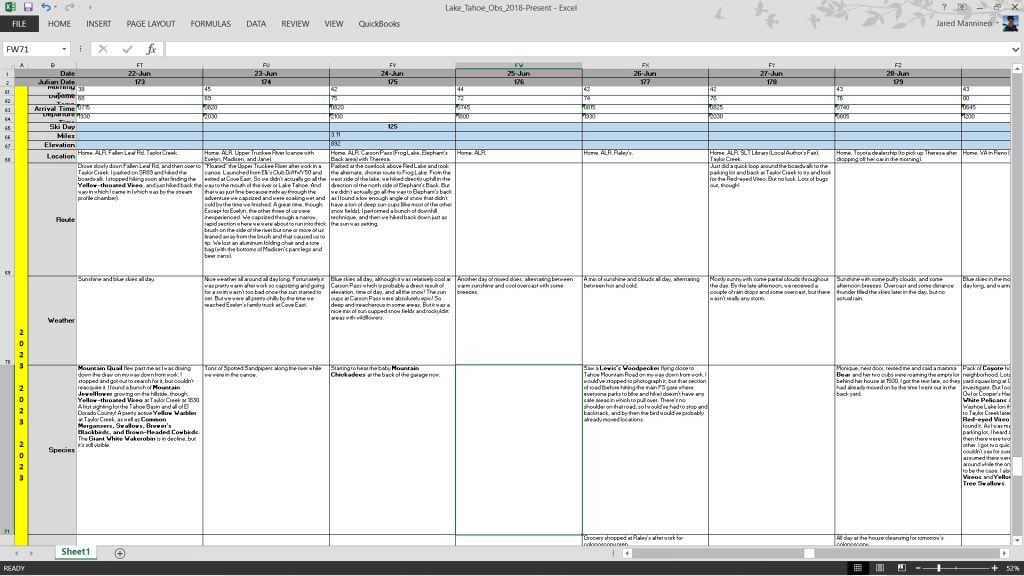

Honestly, I’m not aware of any software dedicated specifically to documenting nature-related observations. However, I have built a spreadsheet where I record my observations using similar data fields to the ones used in a naturalist field journal. And it’s organized by a Julian date calendar. So I record daily observations and make sure that I define where I saw what in the appropriate spreadsheet cell.

Admittedly, I constantly fall behind in recording these daily observations. So I use the spreadsheet in conjunction with physical notes, photographs, audio recordings, and my regular digital calendar. I can then refer to various sources (even years later) to put together a fairly accurate good picture of the day in question. I just wish I had more time to keep on top of it!

Photography

I rely most heavily on photography for recording my observations. In fact, you’ll seldom find me carrying no less than three cameras (including my phone) at any given time. Keep in mind, however, that I’m a big advocate for and user of the naturalist website, iNaturalist. And iNat, as we like to call it, requires media in the form of photographs or audio (mostly for birds) when submitting observations. So I’m always taking pictures of everything, everywhere.

Photography is initially immediate. However, there’s tons of work involved on the backend of the process. Essentially, being a nature or wildlife photographer amounts to becoming an expert at file management (organizing, renaming, editing, submitting).

But photos are worth a thousand words. And they can provide irrefutable proof that you did, in fact, see what you said you saw. That is, so long as you got a clean shot of that Ivory-billed Woodpecker or Big Foot or whatever.

Audio

Recording audio with regard to documenting your nature observations falls into two general categories.

The first approach is to capture actual sounds of nature such as birdsong for use in bird identification. As much as I want to pursue high-quality audio recordings of birdsong, I currently don’t have the money to invest in that type of equipment. So I just use whatever’s at hand, which is either my phone or DSLR.

In fact, I’ll often record a video just so that I can pull the audio from it later to identify the bird in question. It’s not the best quality sound, but it’s usually good enough for an ID. And since the camera is already in my hand I can just hit the video record button to capture that sound.

The second use of an audio recording is to record a voice note about observations that you’ve made. You could accomplish this with a dedicated voice note recorder, an app on your phone, or using the video capture feature on your camera.

I actually use the latter option more than I’d like to admit. This is because it’s usually just easier to hit that video record button than to pull out another device. And, it makes the backend run a little smoother because I won’t have to hook up to my computer the other device to transfer a separate audio file. Once I’ve uploaded the video voice note, I can then record the information on my spreadsheet (and delete the video file).

Video

I’ve begun to capture more video of birds and other critters in recent years. The files are much larger than photographs, but provide far more behavioral information than a static image. And, you can always pull out a snapshot of a frame of the video if you need a photo. The quality won’t be as good as an actual photo, but it’s usually good enough for an ID. That is, assuming you captured clean video in the first place.

Capturing good video, though, is challenging in many cases. For example, most small birds won’t stay put for very long and tracking them is difficult. If you’re using a camera with a zoom lens, the quality of the footage degrades quickly the closer you zoom in. And the more you zoom in, the shakier the footage will become. Using a tripod or monopod will help with stabilization. However, now you’re carrying a tripod or monopod.

I understand that most wildlife photographers do carry a tripod. However, I’m not necessarily encouraging you to become the next National Geographic award winning filmmaker. Rather, I’m simply advocating that you begin to incorporate into your adventures a documentation process for your nature-related observations. And capturing video is one tool that you can use. That said, I would consider it an advanced tool.

Optics

Binoculars, monoculars, spotting scopes and other related optics enable you to reach out and see things in the distance. They also help you see way more details than just with your naked eye.

I know people who are adept at taking photos through spotting scopes with their phones, for example. On the other hand, I’m not one of those people. I always get frustrated trying to focus on the subject and then line up my phone with the scope. That’s why I just use a camera with a telephoto lens!

Websites and Apps

There are countless websites and apps dedicated to plant and wildlife identification. In fact, there are too many to list here. But they’re game-changers for people who want a DIY, learn-about-nature experience. They’re not always accurate, particularly with rare and uncommon species. And many of them require media in the form of photographs or audio files. However, they can do a lot with a little.

For example, the iNaturalist mobile app will provide fairly accurate ID suggestions after uploading a photo from your phone to it. The same goes for bird identification with the Merlin app. After recording birdsong via your phone, the app will offer its best suggestion for identifications. These are really the only websites and apps that I use. And, full disclosure, I prefer iNat’s desktop website way more than the app because it’s more intuitive and useful. You just can’t access all of the website’s features via the app.

Also note the Seek app and iNaturalist’s mobile app are not the same. Seek is designed for kids and features a lot of privacy controls. This may sound appealing to some people. However, you won’t benefit from the thriving community of professionals and other contributors on iNat due to those enhanced privacy features. And, the community is ultimately what makes iNaturalist such a great learning experience.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology maintains the website/app eBird, which is popular among birders. On this site you can document your bird checklists. Cornell also developed the Merlin app and, I believe, you can upload observations via the Merlin app to eBird.

Most likely, you should be able to find a Facebook group dedicated to birds or wildflowers in your area or state. Just make sure that this group is hosted by a reputable person or organization. With that in mind, steer clear if the group or site in question isn’t moderated by a professional. Informal sources such Nextdoor, for example, will lead you astray. Living somewhere for many years doesn’t make anyone an expert in local flora and fauna. Dedicated study, however, does. So the bottom line is that there are too many details involved with most identifications that you simply can’t usually (accurately) know a thing through casual observation alone.

Of course, there are tons of other websites or apps out there (including Google) that’ll help you identify plant and wildlife species.

Most Websites and Apps Lack Accountability

The thing to know about most online resources is that very few of them offer any real feedback or confirmation of your observations.

Most of the apps are just that, apps. Botanists and wildlife biologists don’t create those apps. Rather, a computer programmer assembles an AI engine that scours photos of birds and plants, for example, on the internet. So those apps can get you in the ballpark, but just because they suggest an ID doesn’t actually make it correct.

Ultimately, those suggested IDs are just suggestions. So you’re going to have to dig deeper if you really want to learn about whatever you’re observing.

Even eBird can be unreliable based on your location. That’s because it doesn’t require media. And a lot of uncommon and rare observations never get confirmed since they need to be viewed by a regional moderator. So if the moderator can’t confirm your observation (for whatever reason), it might actually stand no matter how ridiculous the alleged sighting is.

Reference Books

No matter how many online resources become available, there’s nothing quite like having a physical book in hand. I don’t personally carry books with me in the field like a lot of people do. However, they’re invaluable resources for when I’m at home and sorting through my photos.

And just because the taxonomy of some species may change over time doesn’t mean that older reference books aren’t still useful. There’s a good chance that there’s plenty of wisdom in those print books to make them worthwhile to have. Often, they can provide information that you wouldn’t be able to find elsewhere. That’s because they may be the only reliable source of information since nobody has updated them or published any new books regarding your specific topic or location.

Unfortunately, many older reference books went through small print runs since they were relatively specialized. So, many of them have gone out of print for one reason or another. As a result, certain books can be difficult to find and expensive to purchase.

So at some point during your learning process, you’re going to amass a small library of plant and wildlife-related reference books and documents. Trust me. It’s inevitable.

Parting Thoughts

I completely support the DIY approach to learning and experiencing the great outdoors. But you eventually have to acknowledge that no matter how many nature journals you keep or photos you take or books you read, somebody more knowledgeable than you must provide meaningful feedback and to confirm your work.

Learning botany or wildlife biology on your own is no small task. So here’s the thing. Real learning seldom occurs in a vacuum. You need accountability. You need mentors and a supportive community in order to efficiently and effectively learn.

More importantly, you’re cheating yourself out of many “aha!” moments if you’re not seeking feedback of your identifications. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve birded or searched for wildflowers with a mentor who shared some bits of wisdom that completely transformed my understanding of the subject in question. The same experience applies when I post observations on iNaturalist. Every once in a while, an expert will offer some unique information about a species that I just wouldn’t be able to find anywhere else.

So start this whole process of documenting nature-related observations for yourself. But eventually you’re going to want to share those observations with others so that you can receive feedback and accurate ID confirmation.

Remember that learning to identify species will deepen your experience of being outdoors, but so will building a community of fellow outdoor and nature enthusiasts!

Articles About Lake Tahoe Plants and Wildlife

The following Tahoe Trail Guide articles feature information, history, and stories about the various forms of plant and wildlife that you can find at Lake Tahoe.

Lake Tahoe Wildflowers

- Two Major Factors that Determine Peak Bloom Times for Wildflowers at Tahoe

- Tips for Finding Wildflowers at Tahoe

- The Sinister Mustard Flower Rust

- Big Yellow Wildflowers with Big Green Leaves called Woolly Mule’s Ears and Arrowleaf Balsamroot

Trees of the Sierra Nevada

Birds of Lake Tahoe

- The Tree Cleaving Pileated Woodpecker

- How Woodpecker Contribute to Healthy Forests at Lake Tahoe (and other fun facts)

One thought on “Deepen Your Outdoor Experience By Documenting Your Nature-Related Observations”